Peter Geach, Reason and Argument XIII (mit deutscher Übersetzung)

13. Plurative Propositions: Use of Diagrams for Plurative Schemata

We can use diagrams to test the validity of arguments using ‘most’ or ‘half’ as well as ‘every’, ‘some’, and ‘no’. ‘Most Fs are Gs’ is to mean:

More objects in the Universe are FG than are FG’

‘Half the Fs are Gs’ is to mean:

At least as many objects in the Universe are FG as are FG’. Propositions using the quantifiers ‘most’ and ‘half’ are called plurative.

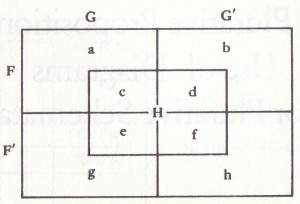

There is a decision method for schemata containing quantifiers of the ordinary sorts and also plurative propositions. We insert in each cell of a diagram a letter signifying the number of individuals of the Universe that are assigned to that cell. Then we construct from our data a set of propositions about the sums formed from these numbers and about whether one sum is or is not greater than another. As before:

If we can represent consistently the premises and the contradictory of the conclusion, we have an invalid schema.

If we cannot do this we have a valid schema.

Examples:

1. Most Fs are Gs; every G is H; ergo most Fs are H.

Test for consistency:

There are more FGs than FG’,

so a + c > b + d (1)

Every G is H,

so a + g = 0, so a = 0, g = 0 (2)

Not (most of Fs are H), i.e. there are not more FHs than FH’,

so c + d = not> a + b (3)

But now we have:

from (1) and (2): c > b + d, and thus c > b

from (2) and (3): c + d not> b, and thus c not> b

CONTRADICTION!

So the schema is valid.

2. More Fs are Gs; most Gs are H; ergo some Fs are H.

Test for consistency:

There are more FGs than FG’s,

so a + c > b + d (1)

There are more GHs than GH’s,

so c + e > a + g (2)

No F is H,

so c + d = 0, c = 0, d= 0 (3)

We now have:

From (1) and (3) a > b

from (2) and (3) e > a + g

Obviously we can find numbers a,b,e,g, to fulfil these conditions: e.g. a = 2, b = 1, g = 1, e = 4. So the schema is invalid.

3. Most Fs are G; most Gs are H; ergo some F is GH.

Test for consistency:

There are more FGs than FG’s, so a + d > b + d (1)

There are more GHs than GH’s, so c + e > a + g (2)

There are more HFs than HF’s, so c + d > e + f (3)

There are no FGHs, so c = 0

By (1) and (4) a > b + d, so a > d

By (2) and (4) e > a + g, so e > a

By (3) and (4) d > e + f, so d > e

So we get a > d, d > e, e > a – a contradiction. So the argument is valid.

13. Plurative Aussagen mit: Verwendung von Diagrammen für Schemata mit Plurativen

Wir können Diagramme verwenden, um die Gültigkeit von Argumenten zu prüfen, die Aussagen mit den plurativen Formen (den Plurativen) „die meisten“ oder „die Hälfte“ ebenso wie mit den üblichen Quantoren „einige“, „alle“ und „keiner“ enthalten.

Die Aussage „Die meisten F sind G“ bedeutet: Mehr Gegenstände im vorgegebenen Universum sind G als G’.

Die Aussage „Die Hälfte der F sind G“ bedeutet: Es sind mindestens so viele Gegenstände im vorgegebenen Universum G wie G’.

Wir nennen Aussagen mit den Quantoren „die meisten“ und „die Hälfte“ plurative Aussagen.

Es gibt ein Entscheidungsverfahren für logische Schemata, die Aussagen mit den üblichen Quantoren und ebenso Aussagen mit Plurativen enthalten. Wir schreiben in jede Zelle unseres Diagramms einen Buchstaben ein, der die Anzahl der Gegenstände des Universums angibt, die dieser Zelle zugeordnet sind. Dann bilden wir aufgrund dieser Datenbasis eine Menge von Aussagen über die Summen, die wir mit diesen Zahlen für die Gegenstände bilden können. Daraus leiten wir durch einfaches Hinsehen Aussagen über die Größenordnung der Summen ab (welche größer/kleiner als die andere ist). Wir gehen wie gehabt vor (siehe letztes Kapitel):

Wenn wir die Prämissen und den kontradiktorischen Gegensatz der Konklusion im Diagramm darstellen könne, ist das Schema ungültig. Wenn wir das nicht können, ist das Schema gültig.

Beispiele:

1. Die meisten F sind G. Jedes F ist H. Ergo: Die meisten F sind H.

Test zur Überprüfung der Konsistenz:

Es gibt mehr FGs als FG’s, also: a + c > b + d (1)

Jedes G ist H,

also: a + g = 0, also a = 0, g = 0 (2)

Nicht (die meisten Fs sind H), das heißt, es gibt nicht mehr FHs als FH’,

also c + d = nicht > a + b (3)

Doch damit bekommen wir Folgendes:

aus (1) und (2): c > b + d, und demnach c > b

aus (2) und (3): c + d nicht > b, und demnach c nicht > b

WIDERSPRUCH!

Folglich ist dieses Schema gültig.

2. Mehr Fs sind Gs; die meisten Gs sind H; ergo: Einige Fs sind H.

Test zur Überprüfung der Konsistenz:

Es gibt mehr FGs als FG’s,

also a + c > b + d (1)

Es gibt mehr GHs als GH’s,

also c + e > a + g (2)

Kein F ist H,

also c + d = 0, c = 0, d= 0 (3)

Damit bekommen wir Folgendes:

aus (1) und (3) a > b

aus (2) und (3) e > a + g

Offenkundig können wir Zahlen a, b, e, g, finden, die diese Wahrheitsbedingungen erfüllen, zum Beispiel: a = 2, b = 1, g = 1, e = 4. Demnach ist dieses Schema ungültig.

3. Die meisten Fs sind G; die meisten Gs sind H; ergo: Einige Fs sind GH.

Test zur Überprüfung der Konsistenz:

Es gibt mehr FGs als FG’s, also a + d > b + d (1)

Es gibt mehr GHs als GH’s, also c + e > a + g (2)

Es gibt mehr HFs als HF’s, also c + d > e + f (3)

Es gibt keine FGHs, also c = 0

Aus (1) und (4) folgt: a > b + d, also a > d

Aus (2) und (4) folgt: e > a + g, also e > a

Aus (3) und (4) folgt: d > e + f, also d > e

Wir erhalten als Resultat: a > d, d > e, e > a – das ist ein Widerspruch. Demnach ist das Schema gültig.